Rising Interest Rates, Part 1, 2 and 3

December 17, 2015 by Brad McMillan

Rising Interest Rates, Part 1: Return To The Natural Level?

DECEMBER 15, 2015

This post originally appeared last spring. With a Federal Reserve rate increase largely expected to happen this week, I want to take a look at what happens when rates start to rise.

Although economic growth appears to be slowing, stocks continue to hit new highs. This may lead one to ask, “How does the market retain its strength?” In fact, much of this strength seems to result from the low interest rates provided by the Federal Reserve (Fed). And although it can’t be said exactly when the Fed will raise rates, expectation is currently high that it will happen on December 16.

So, let’s consider this: What might happen to our investments—stocks, bonds, and everything else—when interest rates are finally allowed to return to their natural level? It is an excellent question, one that will affect everyone who holds these securities (which is to say, almost everyone).

In fact, there are several other questions that should be addressed separately:

1. What is the natural level of interest rates?

2. What’s keeping current rates away from the natural level?

3. Will that stop? When?

4. What happens when it does stop?

5. What does that mean for our investments?

Let‘s start with question 1: What is the natural level of interest rates?

The price of money

Interest rates are actually the price of money. As such, they change with the balance of supply and demand for money. Unlike with most goods, though, there is a monopoly provider of money that can and does change the supply whenever it wants—the Fed or, more generally, the central banks. Interest rates are therefore a market, but a manipulated one.

Despite this manipulation, though, there is such a thing as the natural interest rate, one that balances supply and demand. Economic research has defined it, loosely, as the rate of interest on loans that is neutral with respect to prices, and will not tend to either raise or lower them. (A summary is available here.) This is a vague but useful definition, as it situates interest rates squarely within the Fed’s policy concerns regarding inflation and deflation.

How is the natural interest rate calculated?

Before its conclusion in October 2014, the Fed’s stimulus policy was directed at lowering rates by injecting money into the economy via buying bonds. According to basic economics, increasing the supply of money should lower the price (interest rates). It should also act to increase prices, which suggests the lowered rates are below the natural rate, consistent with the definition above.

Depending on how you calculate it, the natural rate of interest comes in around 3 percent. Given the uncertainty inherent in this type of work, that means somewhere between 2 percent and 4 percent. Note that this is a real rate, so we have to add inflation back in, which gives us a nominal natural interest rate of around 4 percent to 6 percent at the moment, theoretically.

A historical rates comparison

Using the Berra theorem—the well-known economist Yogi Berra’s idea that theory and practice are the same in theory but different in practice—we can then compare this with real historical interest rates to see if it makes empirical sense. The chart below shows the rates paid by inflation-adjusted Treasury bonds.

The general range, of around 2 percent to 3 percent before the financial crisis, supports the economic arguments and the decline during the crisis. Add 2 percent to 3 percent for inflation, and we’re right back to the 4 percent to 6 percent that economic theory suggests. The lower rates during and since the crisis largely appear to be due to a “flight to safety” and central bank actions to flood the markets with money; therefore, they seem less indicative of normal rate levels.

Comparing the natural nominal rate of, say, 5 percent with the current rate of around 2.22 percent for the 10-year Treasury bond tells us that, yes, current rates are well below what they “should” be. The Fed has apparently succeeded in its aim, to lower rates below the natural level, but it’s not quite that simple, which brings us to question 2. We’ll take a closer look at that tomorrow.

Rising Interest Rates, Part 2: Exploring The Gap

DECEMBER 16, 2015

This post originally appeared last spring and is part 2 of a series on what happens when interest rates start to rise.

In part 1 of this series, I explored what interest rates would look like if they returned to their natural level and determined they would be approximately 5 percent on a nominal basis (assuming 2-percent inflation). As the Federal Reserve (Fed) has determined that 2 percent is the target inflation rate, this approximation of the natural rate seems reasonable. Current interest rates, however, are well below 3 percent, resulting in an obvious gap between where the rate is now and where it should be.

So, what’s keeping the rate gap open, when will it close (we may take a step closer this afternoon), and what happens then? (For those who read yesterday’s post, these are questions 2, 3, and 4.)

Looking to the Fed for answers

You’d think these would be simple questions to answer. After all, the Fed spent trillions of dollars buying securities specifically to keep rates down. Surely it has a detailed explanation for how that works, the extent of the effects, and what happens when it pulls back. Right?

Wrong. A commentary from the Cleveland Fed breaks out the components that make up interest rates. Explanations for low rates include:

• Low expected inflation

• A decline in the real interest rate to just about zero

• The higher rate that is required for longer time periods, known as the time premium

Absent is any discussion of the effects of quantitative easing.

A discussion of quantitative easing (QE) from the St. Louis Fed defines and defends it, concluding that the Fed’s program reduced rates by about 75 basis points, or 0.75 percent, through a lower-term premium. For our purposes, we can ignore the details and surmise that, without the Fed’s stimulus, rates would be that much higher: 2.28 percent plus 0.75 percent, for a rate on the 10-year Treasury of 3.03 percent. This is still below the 5 percent we would expect.

The remaining gap must therefore come from low expected inflation and a decline in the real interest rate. The real rate, per the Cleveland Fed paper, dropped from at least 1 percent to 0 percent. When that normalizes, which seems to be happening, the 1-percent shift will be added back to the Treasury rate. Inflation expectations are quoted as declining by about 0.5 percent. Adding these two factors to current rates and the QE adjustment, we’re still below the expected 5 percent by about 50 basis points.

So, why have long-term rates remained muted ahead of the Fed hike?

Given this framework for understanding how interest rates ought to adjust, the end of the Fed’s bond purchases should have pushed rates up. There are three possible reasons why that didn’t happen:

• Although the Fed stopped buying new bonds, it’s still active in the market in a significant way, continuing to reinvest payments and buy bonds to replace the ones that mature. As prices are set at the margin, this may well be suppressing rates.

• Both Japan and Europe have launched their own QE programs. Along with the strength of the dollar, this has made U.S. assets very attractive and is certainly contributing to lower rates. Though the effects of international stimulus wouldn’t be as immediate or as large as Fed stimulus on U.S. rates was, an effect of around 50–75 basis points certainly seems consistent with the data.

• There continues to be strong demand for U.S. Treasuries. When comparing the “safest” yields in the eurozone with U.S. Treasuries, investors will find quite a spread difference between similar maturities. This scenario should help keep a lid on how high rates will go, as demand is expected to remain strong.

The long view

If ongoing low rates are indeed due to the European and Japanese QE programs, they may continue until those programs end, at which time we may see an uptick of 50 to 75 basis points. At this point, though, there’s no sign of either of those programs ending soon.

The adjustment for inflation is somewhat more speculative, but economists continue to expect inflation to remain low. I don’t necessarily agree with that, but for today’s purposes, let’s assume they are right, and any increase would be no more than the 50 basis points assumed in the Cleveland Fed analysis.

All of this is speculative, of course, but it gives us some context for understanding why rates are low, what’s keeping them there, and how and when that will change. With the ongoing stimulus by European and Japanese central banks, the absence of inflation, and the attractiveness of U.S. assets, all factors are pointing toward continued lower rates in the near to medium-term future, even with a Fed rate hike.

We’ll talk about what this means for our investments tomorrow.

Rising Interest Rates, Part 3: What About Investments?

DECEMBER 17, 2015

This post originally appeared last spring and is part 3 of a series on what happens when interest rates start to rise.

As this is the final post in my series on interest rates, it’s time to talk about what everyone is probably thinking: What happens to investments when interest rates rise? This question is especially pertinent given yesterday’s decision by the Federal Reserve on a rate hike.

Effect on the stock market

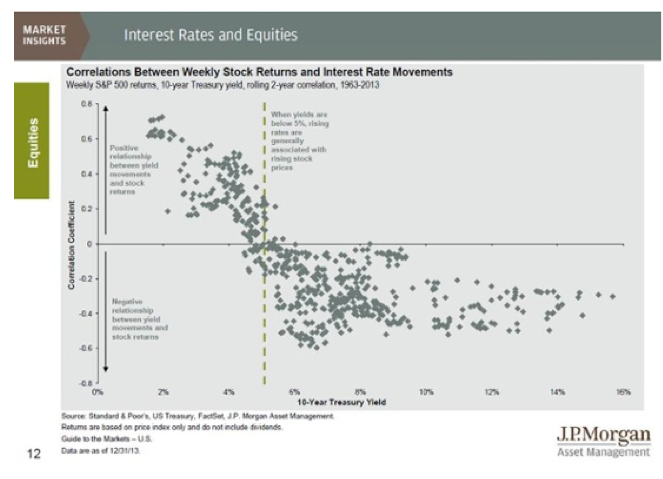

At this point, rising rates actually look like a positive for the stock market, as they reflect a healthier, more normal economy. This chart, which I’ve posted before, shows that stocks have historically performed well during periods of rising rates, as long as rates are below about 5 percent—which, by no accident, is the natural level we identified in part 1.

In theory, stocks should be worth less as rates rise, as the future stream of dividends will be discounted more heavily. Per the Yogi Berra theorem, though, theory and practice are different in practice; the prospect of an improved economy, shown by rising rates, more than offsets this discounting effect. If anything, rising rates may be a positive, at least for the medium term.

Short answer: There are many reasons to worry about the stock market, but rising rates aren’t one of them right now.

Managing risk for bonds

Bonds are the securities most exposed to interest rate changes. Coupon payments are generally fixed, so they’re hit directly by the higher level of future discounting that comes with higher rates. Simply stated, when rates go up, bond prices go down, with bonds that mature later getting hit harder than those that mature sooner. Long is bad when rates rise, if you sell.

That last sentence highlights the two major ways to manage the rate risk a bond owner faces:

• Longer bonds are more exposed to rate increases, so if that’s a concern, stay shorter.

• As with mutual funds, having to sell, or revalue on a daily basis, is also a way to lock in losses.

The second point deserves a bit more explanation. Consider a 10-year bond, and assume that rates rise and the value of the bond drops from 100 to 98. Mutual funds have to value that bond on a daily basis, and investors in the funds will therefore see the value of their holdings drop by the same 2 percent. Investors who hold the bond directly, however, may not care, as they will continue to collect coupon payments and get a par payment at maturity. As long as they don’t sell, they will not have a capital loss.

So, although bonds are exposed to interest rate risk, it can be managed. Bonds also present some opportunities, as any payments can be reinvested for a higher return as rates rise. For those worried about a capital loss, though, managing the duration of your bonds, or owning them directly, can mitigate that risk. (We actually have a team here at Commonwealth to help investors who wish to directly own bonds.)

Short answer: Rate increases will hit bonds, but the risk can be managed in a couple of ways. If capital loss can be avoided, higher rates will allow higher returns on reinvested funds.

What about other assets?

This category includes real estate investment trusts (REITs), master limited partnerships (MLPs), preferred stock, and other financial assets that people buy primarily for the dividend. These will perform somewhere between stocks and bonds, with the growth exposure—possibly good for REITs and MLPs, not usually so good for preferred stock—offsetting the interest rate risk to a greater or lesser extent. It’s not usually possible to manage duration with these assets, however, so investors have one less tool to defend against rate risk.

Short answer: These assets may well see short-term loss due to rising rates, but for many, growth will offset that loss over the longer term.

Plan ahead

Rising rates, at least at this stage of the cycle, can be risky for parts of your portfolio, but they also have upside effects. A rate increase is something to be cautiously welcomed, as it represents a real recovery for the economy and a more stable foundation for future growth. It will require planning and perhaps some changes to your current holdings, but the risk is definitely manageable while we await the new opportunities.

Brad McMillan is the chief investment officer at Commonwealth Financial Network, the nation’s largest privately held independent broker/dealer-RIA. He is the primary spokesperson for Commonwealth’s investment divisions. This post originally appeared on The Independent Market Observer, a daily blog authored by Brad McMillan.